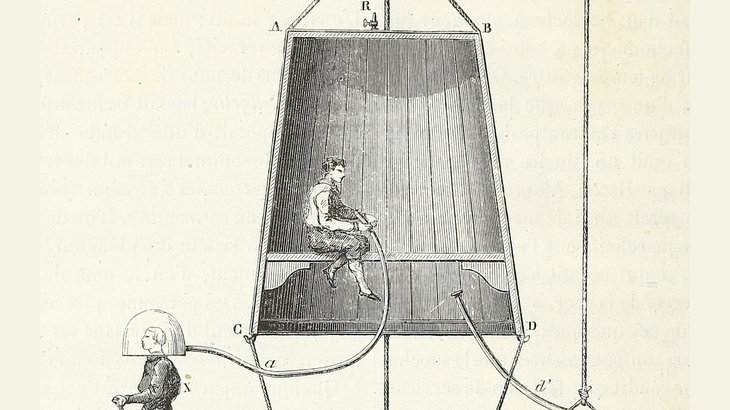

When we began planning a seminar on immersive art, I immediately thought of a diving bell, but not just any diving bell, rather the diving bell mentioned in Bo Widerberg’s 1963 film Kvarteret Korpen (The Raven’s Nest). The main character, Anders, lives in the poor neighborhoods of 1930s Malmö, dreams of becoming a writer, and bickers with his father, a cynical bastard, an old drunk who never succeeded in life—played, incidentally, by the legendary Keve Hjelm—whereupon the father suddenly says that he has invented the diving bell.

What are you talking about? Sit down, you’re making me seasick, replies his son.

But the father stands his ground, claiming that he is the one who invented the diving bell… because how else could he, a sensitive man, cope? He is like Professor Piccard, he has invented the diving bell – and he is sinking.

He is sinking and doesn’t give a damn about his wife, his son, and their circus antics. He is sinking, and there you are on the other side of the glass, and I couldn’t bother.

Watch out, I might break the glass, replies the son.

The father grins sourly. You can’t. The glass is too thick.

It’s been tempered by 20 years of brandy.

With this cheerful introduction, I thought I would like to introduce the topic for the afternoon: immersive art – something that can submerge us into the depths of the unknown sea or lift us up to the skies? What does immersive art entail?

Art, I would argue, has never benefited from categorization into genres, and yet here I am talking about art with a fixed epithet. If we can swallow that bitter pill, I would argue what is currently referred to as immersive art stands on two legs, one of which is situated in the expanded concept of art in the 20th century:

I am referring, among other things, to constructivists and Dadaists of the 1920s, such as Lissitzky’s Proun room or Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau – where art as a setting rather than a work was emphasized. This genealogy continued with the postwar happenings and performances, where the barriers between artwork, artist, and audience were broken down. Artists also explored multisensory environments using projections, sound, and light.

The second leg—or perhaps we should call it a joystick?—can be found in commercial entertainment and arcade games. Simulations were first developed as military training applications and now constitute a whole set of unreal “realities”:

VR-AR-MR-XR—the jumble of abbreviations is neither well-defined nor consistent, which makes it all the more confusing, and here Dr. Sandra Gaudenzi will soon help us navigate through this jungle.

Keep in mind that these technologies are developed in and for a capitalist system, and it is not entirely unexpected that they are primarily designed to operate through isolation rather than connection. Whether they facilitate microsurgery, drone warfare, or gaming, the dominant industry model is individual use.

A telling example of this is your Facebook developer standing alone on stage, wearing smart glasses and suggesting that we invite our “AI buddies” to the Metaverse.

In this regard, art has an important role to play—rather than being the diving bell that the father in Raven’s endhad devised after 20 years of drinking, an isolating shell that allowed him to avoid facing his family—art, with the social knowledge formed by the 20th-century art scene, may hijack these technologies and return them to shared experiences. Something that I know we will see several examples of this afternoon.

It appears impossible to avoid talking about Plato, especially when approaching realities through projections. In 1992, computer scientist Carolina Cruz-Neira designed the first immersive system in the digital age. Appropriately, it was recursively named CAVE – Cave Automatic Virtual Environment – a room with rear projections in all directions where the user would be surrounded by information, a kind of immersive learning method. CAVE was a literal embrace of the illusions that Plato dismissed in his aristocratic contempt for democracy and the common man who didn’t understand that what he perceived as reality was only make-believe.

Technology-driven “immersive” installations have grown in popularity. Projects run by artists, artist collectives, and production companies range from sophisticated installations with artistic merit to animated retrospectives of impressionist painters with expired copyrights that have increased the financial incentives.

As usual, our era is searching for the new, but immersive art—a word derived from the Latin immergere, meaning to dip or sink into something—has a long history, if we consider aesthetic artifacts that are in some way enveloping, or when the boundary between artwork and surroundings dissolves and becomes an all-encompassing experience. I would even argue that immersiveness was part of the original job description of art.

This is particularly true in two fields: religion, where artists have worked with church interiors, creating visual worlds that cover the entire field of vision through dome paintings, iconostases, and frescoes; and also for secular power, where artists have been engaged to fill castles and manors to the brim with portraits, landscapes, and murals as part of the overall architecture.

Perhaps one could venture to say that the artwork as a distinct object, i.e., the non-immersive artwork, was the real aesthetic innovation that followed in the wake of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, when churches and castles were emptied of their artifacts, taken out of their natural context, and exhibited as free-floating objects and signifiers in their own right.

The aesthetic autonomy that was secured by then is well worth remembering now that museum directors and curators are inviting visitors to move beyond “passive viewing” and instead make visitors “active participants in inclusive narratives.”

This emphasis on participation, on not being passive, appears to be a modern-day counterpart to the search for authenticity that erupted in connection with industrialism—when mass production and proletarianization, the interchangeability of everything, led people to seek out the unique, to distinguish between the original and the copy—which had a particular impact on how people approached art.

The original art work still plays an important role in art – especially in the art market, which lives by its own rules and can be compared to the economic bubbles of the financial sector. For the average person’s wallet, the increasingly elusive original art work is unaffordable and therefore plays a less and less important role.

Participation – in the age of tech giants – is the new black, and being passive is something bad. We look busyeven when we’re mindlessly scrolling through Instagram. A kind of aesthetic hierarchy has been established where inappropriate inactivity is a sign that you have given up, that you are not part of the development and will therefore be left behind. One could turn the tables and argue that this is precisely why non-participation can be the primary mode of resistance – refusing to go with the flow, not even swimming against the tide, but simply stopping and doing nothing.

In this respect, too, art can play a decisive role, but it may also require that art insists on doing nothing of value – for it is easy to imagine the therapeutic benefits, helping people to relax rather than kicking back against a society that does not allow us to relax and switch off. Perhaps it would be beneficial to reread In Praise of Laziness by the late Yugoslavian artist Mladen Stilinović, who argued that artists in the West seemed incapable of creating real art because they had not mastered the art of being lazy.

A 2022 New York Times article “The Rise of Immersive Art – why are tech-centric, projection-based exhibits suddenly everywhere?“ outlines a scene we all recognize: when children act as the harshest of art critics at an exhibition – but rather than saying ”this was boring, can we go now, Dad?“ their little mouths gape and they say ”wow, this was trippy!".

Without going into how conspicuous drug-related slang has found its way into the vocabulary of the very youngest, it is worth reflecting on the incentives that arise when art elicits reactions such as “far out,” “cool,” and note that there are crucial distinctions in the strict hierarchies of affirmation between a “that was neat” and a more empathetic “oh, how wonderful.” Even an Ayahuasca trip can generate a dizzying aesthetic experience, but the question is how well it can be integrated into life in general – when you leave the diving bell and it’s time to tackle the growing pile of bills and all the countless work meetings that prevent you from ever doing your job.

The concept of quality in contemporary art has shifted from universal, objective standards (such as Renaissance harmony) to subjective, contextual interpretations, challenged by postmodernism, “new art history” and social theory – the focus has shifted from inherent beauty to conceptual depth, social criticism and individual expression, where “quality” becomes a contested field of tension between skill, concept, market value and cultural relevance, rather than a fixed aesthetic ideal – a complicated story, quite simply.

Since it is virtually impossible to say with certainty what is good or not so good art, socio-economic success often becomes the exclusive benchmark. Through circular reasoning, success can become a receipt for quality, or at least be expressed with a euphemism such as the concept of “relevant.”

I will conclude with a case study of such success.

The art collective TeamLab was founded in 1998 and today consists of approximately 600 employees in the fields of art, technology, and architecture. Their breakthrough came in 2011 via the Singapore Biennale, followed by a strategic partnership with PACE Gallery in New York in 2014, which enabled international expansion.

TeamLab has sold works to institutions such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the National Gallery of Victoria, and the Asia Society Museum in New York. They opened TeamLab Borderless in Tokyo in 2018, which became the world’s most visited single-artist museum with 2.3 million visitors in its first year.

Following the success in Tokyo, the collective expanded with TeamLab Borderless Shanghai (6,600 m², approximately 50 works) in November 2019 and a third permanent installation in Macao (5,000 m²) in January 2020. The business model is based on scalable digital art, high visitor frequency, and strategic partnerships for global expansion.

For five years in a row, the Serpentine Gallery in London has published a so-called strategic briefing that “provides analytical and conceptual tools for building the cultural infrastructure of the 21st century.” The 2020 report presents the concept of “art stacks” – artist-led organisations that integrate functions normally scattered between galleries, museums, technology companies and other actors. By building their own revenue streams, often through ticket sales, they achieve autonomy from traditional sources of funding. One example cited is TeamLab.

The term “stack” is borrowed from software development, where it describes a vertical integration of technologies and tools that together form a complete system—for example, how a so-called full-stack developer for web applications combines the entire chain from database, server, and programming language to interface design. In the same way, art stacks build a vertical integration of all parts of art production: from creation and technical infrastructure to exhibition, marketing, and commercialization—all under the same umbrella.

The report identifies two challenges: art stacks require team-based work rather than the individual artist model that dominates the art world, and they presuppose a commercialisation that many artists have historically rejected. The model resembles circuses and amusement parks with mass market appeal through ticket sales, raising questions about what qualifies as “art” when the scales and business models are more reminiscent of the entertainment industry than traditional art institutions.